Is The Wi-Fi Working For You? Does it Ever?

Wi-Fi (Wireless Fidelity, though nobody can quite explain what’s particularly “faithful” about it) is Earth’s charmingly primitive attempt at wireless data transmission. It represents roughly the same technological advancement as two tin cans connected by string, except the string is invisible, frequently breaks, and requires you to turn everything off and on again.

The Basic Concept

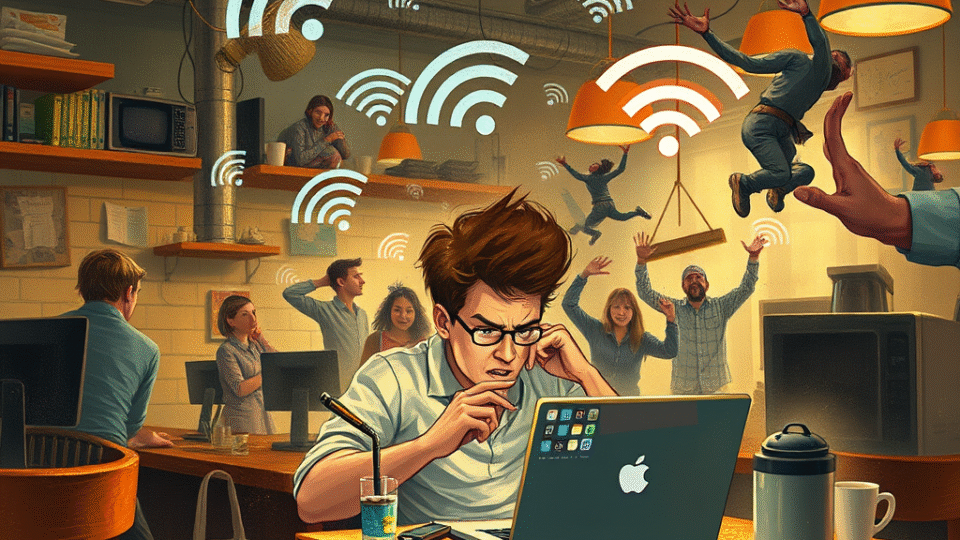

Wi-Fi works by converting information into radio waves and flinging them desperately through the air in the hope that they’ll reach their intended destination. This is rather like trying to have a conversation by shouting across a crowded restaurant while someone operates a blender next to your ear. Sometimes it works. Often it doesn’t. Humans have accepted this as normal.

The technology operates on the revolutionary principle that if you can’t see the wires, you can pretend they don’t exist—a philosophy Earth humans also apply to their problems, their calories, and their credit card debt.

The Reliability Problem

Wi-Fi signals are notoriously temperamental. They can be disrupted by:

- Walls (particularly inconvenient, as humans insist on building these everywhere)

- Other Wi-Fi signals (creating a sort of invisible shouting match)

- Microwave ovens (because apparently both technologies share the same frequency, which is like building a highway and a railway on the same strip of ground)

- Rain

- Sunshine

- Thoughts of using the internet

- The absence of thoughts about using the internet

- Tuesdays

- Nearby flatulence

The standard human response to Wi-Fi failure is a ritual known as “turning it off and on again,” which works approximately 60% of the time for reasons nobody fully understands. This has led to a quasi-religious belief that technology responds to percussive maintenance and aggressive sighing.

Password Archaeology

Accessing Wi-Fi requires a “password,” which humans inevitably write on a piece of paper stuck to the router, thereby defeating the entire purpose of having a password. These passwords are typically either “password123” or an incomprehensible string of characters that would take less time to crack than to type correctly.

Public Wi-Fi establishments often provide passwords like “Coffee2024!” or “AskStaff,” the latter being particularly unhelpful when the staff member is seventeen and started their shift five minutes ago.

What The Civilized Galaxy Uses

The rest of the galaxy abandoned radio-wave-based data transmission approximately 8,000 years ago (Galactic Standard Time) in favor of Quantum Entanglement Networking, or QEN.

QEN works by entangling particles at the quantum level, allowing instantaneous data transfer across any distance without any of that tedious “traveling through space” business that radio waves insist upon. There are no passwords, no signal strength issues, and no need to position yourself in the northeast corner of the room while standing on one leg.

More advanced civilizations use Probability Stream Integration, which doesn’t so much transmit data as ensure that the data was always already where it needed to be. This technology is so reliable that these civilizations have forgotten what the word “buffering” means, assuming they ever knew it in the first place.

The Galactic Council briefly considered introducing QEN to Earth in 2010, but after observing humans argue about whether five bars or four bars of signal strength was better, they decided Earth wasn’t ready. They were right.

The Future

Earth scientists are currently working on “6G” technologies, which promise to make everything faster. This is rather like promising to make a hamster wheel more efficient—technically true, but missing the larger point that you’re still running in a circle.

Until Earth discovers how to harness quantum entanglement (estimated arrival: 2247, or possibly never), humans will continue to gather in specific corners of their dwellings, holding their devices at odd angles, and muttering “Is the Wi-Fi working for you?” to anyone within earshot.

The answer, statistically speaking, is “No. Have you tried turning it off and turning it on again?”